When the world began to digitize in the 1990s, the Internet was still associated with promises: open access, free content, no intellectual property. Anyone who once believed in them can only elicit an uptight laugh today. The belief in genius, receiving the idea like a medium from a greater power, seemed to simply dissolve in the digital spheres of the WWW. Of course, this void was accompanied from the beginning by the question of how to monetize the digital circulation processes. Very prominent at the time were the cries for help from the music industry, which was worth billions and whose CD sales were suffering badly from the appeal of illegal downloads. But there was also a great deal of concern in the arts and journalism about the category of intellectual property as a prerequisite for making a living.

Social media has changed the dynamics of the web significantly. Today we have to deal with sometimes fierce culture wars, fake news and trolling; always accompanied by algorithms and artificial intelligences that interfere with our habits and determine us as a social product of global megacorporations. In all this hubbub, the desire for truth and authenticity is growing among many. And maybe that’s why everyone is talking about the blockchain, a technology that is capable of doing just that and answers the question of intellectual property in the digital space.

Investment-HYPE Around digital IMPRINTS

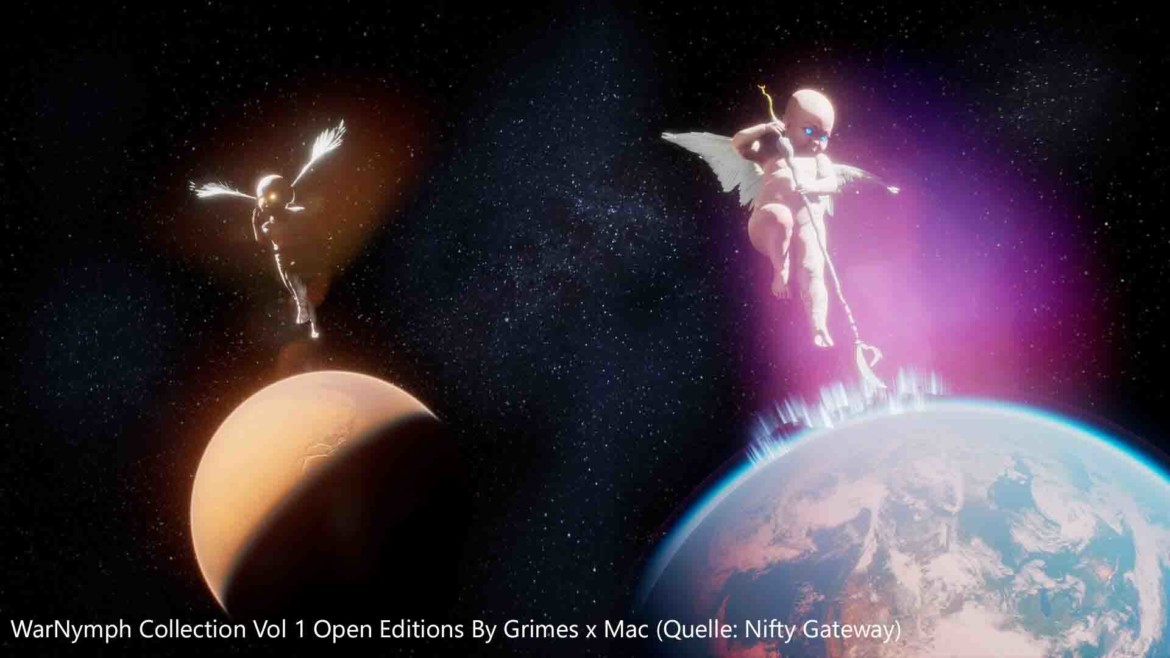

So far, blockchain has been known mainly through bitcoin. But now the news is piling up about the sales of so-called NFT art, which also use blockchain technology and have started an investment craze. The most famous among them are certainly the artist Grimes, who earned almost 6 million US dollars with NFT artworks within a few hours, and the American graphic designer Beeple, who auctioned his artwork for a fabulous 69.3 million US dollars.

NFT stands for “non-fungible token.” NFTs can be of any file format and receive an imprint in a computational process that is stored in the blockchain, where it remains recognizable as the original. The file itself does not reside in the blockchain, but on a separate server. The imprint refers to this file and stores its transaction history. With each transaction, a new block with the current information is added, lining up as if on a chain. Each element refers to the entire chain by being associated with a so-called hash value. Every person involved, starting with the originator, stores this chain and in this way confirms every previous and every future transaction. If an element is manipulated, the hash value for this element changes and cannot be assigned to the chain of the original. Such an original can still be copied and thus circulate in the network, but the imprint remains unique and secures the original status.

MarkET for Digital ART

For the art market, this technology means nothing less than that digital objects are given a market value and thus become tradable – although strictly speaking only the imprint generates the value and is traded, not the artwork itself. But that doesn’t deter collectors and galleries from feeding even private art collections into the blockchain – creator and owner coincide strangely here.

But artists can also benefit from this and sell their works in this way, as in a gallery, in order to receive financial support from their followers. Musicians such as Mau5trap or the Kings of Leon have already used the blockchain to sell their music – sometimes with an individual touch – as NFTs. Unfortunately, the interest in NFTs is mainly concentrated on already successful and famous artists, so that newcomers have hardly benefited from this so far. From a purely technical point of view, this is very conceivable, but it remains to be seen how the blockchain will be accepted by the creative industry.

The Original in Plural

The digital blockchain has a key advantage over analog trading areas: there can be multiple originals. The artists can either offer a certain number of minted works themselves. Or they determine a time window in which their work is available indefinitely. With such a time-limited drop, it is up to the consumers how many originals there will be. These drops are usually announced on social media, sometimes with only 15 minutes notice. Since everyone can see how many originals have resulted from such a drop, it makes no sense to put manipulated coins into circulation, since they cannot be traced back to the originally minted hash value. Viewed in this way, it could be said that an NFT is created by a transaction in the first place.

The idea with technically reproduced originals is not new and comes from pop. A drop follows the same logic as a pressing of records; if it is sold out, you have to go to marketplaces – analog or digital – and look for it. Again, there was not the one original, but just the number of one pressing, all of which have the same value, apart from their wear and tear. And yet, of course, there is a serious difference: the record offers an experience that goes beyond playing an mp3 file – quite independent of the personal evaluation of that experience. But since NFTs are an artificial scarcity, which strictly speaking is not one, because the works can and do circulate freely through the net (if no one knows the work, it can’t become famous), the link to the imprint offers no added value beyond mere capital investment.

Hype creates pressure to miss out, and therefore has its own unique dynamics. Thus, it is currently difficult to assess what blockchain means for the creative industry and what opportunities it offers for smaller and less successful artists*. The technical potential is definitely there, and blockchain is probably the most exciting development in the digital space. The fact that there is a lot of material for technological dystopias in here and that we can’t quite assess whether we are already in one, is something we will have to learn to put up with.

Leave a Reply